On the evening of that first day of the week,

when the doors were locked, where the disciples were,

for fear of the Jews,

Jesus came and stood in their midst

and said to them, “Peace be with you.”

When he had said this, he showed them his hands and his side.

The disciples rejoiced when they saw the Lord.

Jesus said to them again, “Peace be with you.

As the Father has sent me, so I send you.”

And when he had said this, he breathed on them and said to them,

“Receive the Holy Spirit.

Whose sins you forgive are forgiven them,

and whose sins you retain are retained.”

Thomas, called Didymus, one of the Twelve,

was not with them when Jesus came.

So the other disciples said to him, “We have seen the Lord.”

But he said to them,

“Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands

and put my finger into the nailmarks

and put my hand into his side, I will not believe.”

Now a week later his disciples were again inside

and Thomas was with them.

Jesus came, although the doors were locked,

and stood in their midst and said, “Peace be with you.”

Then he said to Thomas, “Put your finger here and see my hands,

and bring your hand and put it into my side,

and do not be unbelieving, but believe.”

Thomas answered and said to him, “My Lord and my God!”

Jesus said to him, “Have you come to believe because you have seen me?

Blessed are those who have not seen and have believed.”

Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples

that are not written in this book.

But these are written that you may come to believe

that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God,

and that through this belief you may have life in his name.

John 20: 19-31

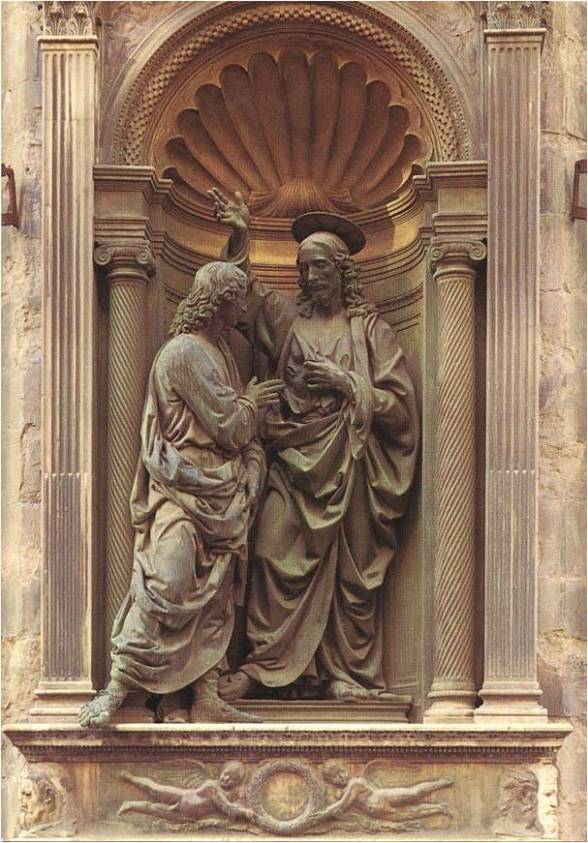

Christ and St. Thomas, by Andrea del Verrocchio, is a bronze sculpture created for Orsanmichele, a building in Florence, Italy. Orsanmichele was a market and warehouse for grain reserves, and in the fifteenth century a series of statues were commissioned by the Florentine guilds for the fourteen architectural niches that surround the building.

Because of these statues, Orsanmichele is considered to be one of the major sites of Renaissance sculpture. Verrocchio’s Christ and St. Thomas was commissioned in 1467 by the Universita della Mercanzia, an organization which regulated trade and guilds in Florence.

Andrea del Verrocchio was a sculptor and painter who later became a teacher of Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli, among others, and whose influence was far-reaching. Born in the early 1430s in Florence, he benefited from the early Renaissance advances in art there by such luminaries as Donatello and Ghiberti, and also from the explosion in patronage that occurred in Florence at the time. He became one of the favored artists of the Medicis, that illustrious and powerful family whose contribution to Florentine art is incalculable. Verrocchio’s concern for spatial representation in sculpture, and his inventiveness in exploring the issue of multiple viewpoints, as evidenced in Christ and St. Thomas, continued to influence artists into the later fifteenth century.

The creation of Christ and St. Thomas is well-documented, with Verrocchio’s name first appearing in connection with it in January of 1467. It is unknown for certain whether it was Verrocchio or the Mercanzia who decided upon the subject matter. It is known, however, that the Mercanzia board members were all closely related to the Medicis and involved in the political factions of the time. They may have chosen the subject because St. Thomas was a favorite saint of the Medicis. The biblical story of Christ and St. Thomas was thought to personify justice, mercy and truth. There was a campaign at the time promoting Lorenzo de Medici’s rule as the exemplification of these qualities. There also may have been a purposeful identification of the Medicis with the wisdom of Christ and the error of St. Thomas’s doubt with their opponents. The grouping may therefore have had as much a political as a spiritual function.

(Click on images for larger views)

Verrocchio’s Christ and St. Thomas follows the pattern of previous depictions of the story, with Thomas in profile on the viewer’s left, reaching out with his right hand; and with Christ shown frontally on the right, holding his right hand over Thomas and exposing his wound with his left hand. However, Verrocchio’s composition is a departure from the standards normally seen in niche sculpture of the time. Previously, such a work would have been constrained within its architectural setting. Instead Verrocchio has boldly placed the statue of St. Thomas actually outside of the niche, intruding into the viewer’s space. His feet are on the exterior ledge and he appears to be advancing into the niche, toward Christ, who stands on a slightly higher level on the entablature, making him majestically taller than Thomas. This makes the niche itself appear to be more than a neutral, architectural setting, and it becomes a dynamic space within which the narrative event is played out.

The statues of Christ and St. Thomas exhibit a fresh naturalism and movement seldom seen in previous sculpture since antiquity. The gestures of each of the figures give the illusion that they are moving toward one another. The right hand of St. Thomas reaches out tentatively towards Christ’s side to touch the wound that Christ displays by tenderly pulling his garment open with his left hand, while holding his right hand over the head of Thomas in a dynamic gesture. Because of the perpendicular placement of the figures and their sense of movement toward one another, they appear as if they can be viewed from multiple angles, rather than just frontally. This is particularly true of the figure of St. Thomas, because of its placement and angle.

Verrocchio apparently utilized natural lighting in such a way that both the reaching hand of Thomas and the raised hand of Christ are naturally illuminated, while their respective backgrounds remain darker, thus highlighting their gestures of faith and majesty, respectively, through the use of chiaroscuro. It is thought that Verrocchio may have worked with wooden and wax models of the scene to create these effects of light and shadow.

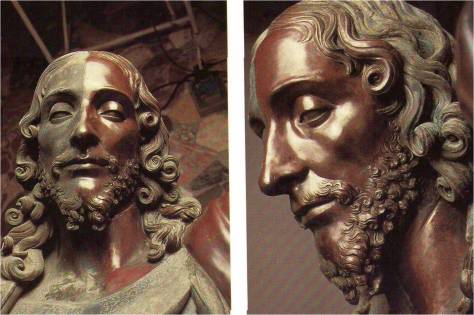

The figure of St. Thomas was finished nine years later than that of Christ and this is reflected by the differences in the drapery styles. The robe of Christ is smoother, with the folds more sharply delineated, while that of St. Thomas is broken into more rounded folds and angles. Despite these stylistic differences, however, Verrocchio has added to the symmetry of the work by creating echoes and harmonies in the drapery of the figures. The trajectory of the folds, the angle of Thomas’s leg, the gestures of the right hand of Thomas and left hand of Christ, and the gaze of both figures, all point toward Christ’s wound which lies at the approximate center of the niche, making it both the physical and spiritual center of the sculpture.

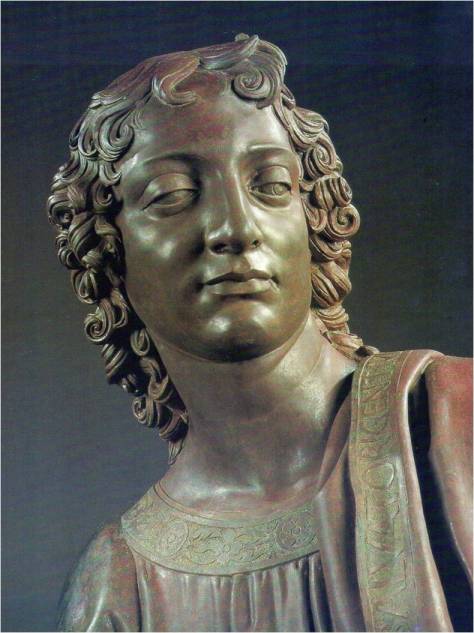

Verrocchio’s pupil, Leonardo, stressed that the movement of a sculpture must depict “great immediacy” and “fervor.” The Christ and St. Thomas sculpture accomplishes this by the gestures and modeling of the figures, and by the choice of the gilded Latin inscriptions that are included. On Thomas’s cloak are the words, “My Lord and My God” which he exclaims in the Gospel of John after touching Christ’s wound. Christ’s response, also inscribed, is “Because you have seen me, Thomas, you have believed; blessed are those who did not see and believed.” Verrocchio has captured Thomas at the moment immediately before he touches Christ’s wound, and in his face we can see the hardened skepticism of the doubter just beginning to transform in awe.

The simultaneous movements of his body as it twists towards Christ, while his right hand reaches across and his left foot steps in, show his eagerness to believe. The agitated curves of the folds and swags of Thomas’s robes all emphasize his movement and point towards his hand aiming at Christ’s wounded side. The viewer knows that in the next instant Thomas’s doubt will be transformed into absolute faith, and Verrocchio has brilliantly depicted the tension of the moment. Adding further to this dramatic tension, the right arm of Christ is raised in the traditional pose of triumphal judgment, while his left hand tenderly exposes and offers his wounded side, showing both his remonstrance and his mercy. The end result is a sculpture which conveys an emotional resonance that is bold and innovative for the art of the time, while still showing Classical restraint.

Verrocchio’s choice for the portrait of Christ was based upon an apocryphal description that was influential throughout the Medieval and Renaissance periods. This literary work, supposedly written by a Roman named Publius Lentulus, describes Christ as having long hair with a center part, a large nose, and a beard divided in two.

The Verrocchio sculpture subsequently became the model for hundreds, possibly thousands of imitations in the ensuing few decades. The pose of St. Thomas is nearly identical to a figure on the Arch of Trajan at Benevento, and although there is no certain documentary evidence that Verrocchio visited the town, it is possible that he used the figure as a model.

The creation of a narrative group rather than a single figure caused technical challenges for the artist. Because of the limited amount of space in the niche, Verrocchio cast the sculptures with hollow backs.

Although they appear to the viewer to be fully rounded, they are in fact very high relief. In addition to making the grouping fit the space of the niche, this inventive decision made them less expensive and simplified the casting process.

The statues were unveiled on June 21, 1483 to wide acclaim. Although they have continued to influence and inspire artists in the 500+ years since then, time inevitably took its toll on their beauty. The bronze had become dull and damaged from acid rain and parts of both figures were covered in centuries of pigeon droppings, reducing Verrocchio’s masterpiece to a “piteous state.”

A careful restoration of the figures was undertaken in 1988, with splendid results. The figure of Christ, especially, because it was more protected within its niche, was able to be restored almost completely to its original, glowing bronze finish.

The statue of St. Thomas was more problematic, but it, too, was cleaned and its appearance significantly restored. Sadly, the image now displayed in the exterior niche is a copy of the original sculpture group. The statues were not returned to their niche, but were placed in a museum inside Orsanmichele to protect them from further damage.

Verrocchio went on to produce many more works of art, but the Christ and St. Thomas stands today as his consummate and most influential masterpiece. The precise date of his death is unknown, although it was sometime in mid-1488, before the advent of the High Renaissance. Without his innovative techniques of physical realism and bold spatial use, his effects of chiaroscuro, and the emotional expressiveness of his composition, perhaps the achievements of the High Renaissance would not have been possible.

Many of us can relate to the disbelief of Thomas when he is told of the Resurrection, especially in our modern scientific age. We refuse to believe unless we can have some proof. Pope Gregory I, who was pope from 590-604, wrote the following about Thomas and our own disbelief:

“Thomas, one of the twelve, called the Twin, was not with them when Jesus came.” He was the only disciple absent; on his return he heard what had happened but refused to believe it. The Lord came a second time; he offered his side for the disbelieving disciple to touch, held out his hands, and showing the scars of his wounds, healed the wound of disbelief. Dearly beloved, what do you see in these events? Do you really believe that it was by chance that this chosen disciple was absent, then came and heard, heard and doubted, doubted and touched, touched and believed? It was not by chance but in God’s providence. In a marvelous way God’s mercy arranged that the disbelieving disciple, in touching the wounds of his master’s body, should heal our wounds of disbelief. The disbelief of Thomas has done more for our faith than the faith of the other disciples. As he touches Christ and is won over to belief, every doubt is cast aside and our faith is strengthened. So the disciple who doubted, then felt Christ’s wounds, becomes a witness to the reality of the resurrection. Touching Christ, he cried out: “‘My Lord and my God.’ Jesus said to him: ‘Because you have seen me, Thomas, you have believed.'” Paul said: “Faith is the guarantee of things hoped for, the evidence of things unseen.” It is clear, then, that faith is the proof of what cannot be seen. What is seen gives knowledge, not faith. When Thomas saw and touched, why was he told: “You have believed because you have seen me?” Because what he saw and what he believed were different things. God cannot be seen by mortal man. Thomas saw a human being, whom he acknowledged to be God, and said: “My Lord and my God.” Seeing, he believed ; looking at one who was true man, he cried out that this was God, the God he could not see. What follows is reason for great joy: “Blessed are those who have not seen and have believed.” There is here a particular reference to ourselves. We are included in these words, but only if we follow up our faith with good works. The true believer practices what he believes. But of those who pay only lip service to faith, Paul has this to say: “They profess to know God, but they deny him in their works.” Therefore James says: “Faith without works is dead.” – from a homily by Pope Saint Gregory the Great

Fantastic article. Thank you for this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike

[…] 9. Doubting Thomas […]

LikeLike

Great article. I am doing a research paper on this sculpture and was wondering what some of your references were for information and photos.

LikeLike

I actually wrote this paper as an undergrad and found the sources myself. So should you, that’s why it’s called a research paper. Good luck!

LikeLike