|

Christendom’s earliest basilica and home of the Popes for a thousand years St. John Lateran on the Caelian Hill.

Google map of Rome with the Lateran circled St. John Lateran is Christendom’s earliest basilica. Ordered by Rome’s first Christian Emperor, Constantine the Great, it became the Popes’ own cathedral and official residence for the first millennium of Christian history.Today, standing before the basilica’s ponderous eighteenth- century facade, assailed by ear-splitting Roman traffic snarls on every side, we can hardly imagine this as the cradle of our religious heritage. A visitor should glance upwards. Towering against the (usually) cobalt-blue Roman sky, a 7-meter high statue of Christ, flanked by saints and doctors of the Church, triumphantly displays the Cross of Redemption.It was to Jesus the Savior that Constantine dedicated the original church, confirming Christ’s superiority over the Capital’s pagan gods and assuring the worldwide expansion of the Christian religion.

THE ROMAN EMPIRE BECOMES CHRISTIAN

With the ascent of Constantine as Emperor of Rome (306-337), the days of bloody Christian persecutions (see Inside the Vatican, January 1996) came to an end. Placed at first on an equal footing with paganism, Christianity soon became the official religion of the Roman Empire.

Constantine was the son of Constantius I, Roman Emperor of the West (305-6), and Helena, a woman of obscure origins, whose fervent conversion to Christianity, and legendar finding of the True Cross, won her sainthood. After defeating his rival Maxentius, son of an earlier emperor Maximian (286-305), at the Milvian Bridge in Rome. (312), Constantine established himself as the undisputed ruler of the Western Empire.

Blog author with remains of colossal statue of Constantine the Great, now in the Capitoline Museum The night before this battle, Constantine’s earliest biographer Eusbesius tells us, the emperor saw a cross of light in the heavens and the words In Hoc Signo Vinces (“by this sign you shall conquer”). His soldiers went into battle bearing the Christian monogram on their shields, rather than the Roman eagle, and a standard of Christ’s cross carried before them. From that time, as he won battle after battle and consolidated his rule over the empire in East and West (324), the Emperor claimed to be fighting in Jesus’ name, as the champion of the Christian faith.

Vision of the Cross, School of Raphael, 1520-24, Hall of Constantine, Rooms of Raphael, Vatican Museums, Rome The Edict of Milan (313) secured Christians’ freedom and legal recognition. By imperial edicts, Constantine restored Christians’ property and strengthened the Church hierarchy (without giving too much offense to Rome’s influential pagans!). He ordered basilicas built over the cellae memoriae marking St. Peter’s, St. Paul’s, and other martyrs’ tombs. And he donated his personal property, received in dowry from his wife, for the first papal cathedral and residence in Christian history. So begins the story of St. John Lateran.

HISTORY

It was to Pope Melchiade (311-314) that Constantine gave the palace on Monte Celio, formerly property of the patrician Laterani family (hence the basilica’s appellation “Lateran”), which his second wife Fausta (Maxentius’ sister) had brought to the marriage. Soon after, the Emperor razed the adjoining imperial horse-guards barracks (allegedly the equites singulares had supported Maxentius against Constantine) and commissioned the construction of the world’s first Christian basilica on that site.

Henceforth, the Lateran palace, known as the Patriarchate, was the Pope’s official residence until the fifteenth century. The basilica, consecrated in 324 by Melchiade’s successor, Pope Sylvester I (314-335), was dedicated, by will of the Emperor, to Christ the Savior. In the tenth century, Pope Sergio III (904-911) added St. John the Baptist, and in the twelfth century, Pope Lucius (1144- 1145), St. John the Evangelist, to the basilica’s dedication.

In the course of its history, St. John Lateran suffered just about as many disasters and revivals as the papacy it hosted. Sacked by Alaric in 408 and Genseric in 455, it was rebuilt by Pope Leo the Great (440-461), and centuries later by Pope Hadrian I (772-795). Almost entirely destroyed by an earthquake in 896, the basilica was again restored by Pope Sergius III (904-911). Later the church was heavily damaged by fires in 1308 and 1360.

When the Popes returned from their sojourn in Avignon, France (1304-1377), they found their basilica and palace in such disrepair, that they decided to transfer to the Vatican, near St. Peter’s. (That basilica, also built by Constantine, had until then served primarily as a pilgrimage church.)

Pope Sixtus V (1585-1590), in one of his frenzied urban renewal projects, tore down St. John Lateran’s original buildings, replacing them with late-Renaissance structures by his favorite architect Domenico Fontana. Later, Pope Innocent X (1644-1655) engaged one of the Baroque’s most brilliant architects, Francesco Borromini, to transform St. John Lateran’s interior in time for the Jubilee of 1650. Finally, Pope Clement XII (1730-740) launched a competition for the design of a new facade, which was completed by Alessandro Galilei in 1735.

Of the original Lateran basilica and palace, only the Popes’ private chapel, the Sancta Sanctorum (See Inside the Vatican, August-September 1995) remains. Sixtus V removed this magnificently-frescoed shrine to what has become a grimy traffic island. As an approach to the chapel, Sixtus moved from the Lateran Palace the Scala Santa, the staircase which Jesus is believed to have ascended to Pontius Pilate’s palace in Jerusalem, and according to tradition, was brought to Rome by St. Helena herself.

Many important historic events have taken place in St. John Lateran, including 5 Ecumenical Councils and many diocesan synods. In 1929 the Lateran Pacts, which established the territory and status of the State of Vatican City, were signed here between the Holy See and the Government of Italy.

The offices of the Cardinal Vicar of Rome now occupy the Lateran Palace. On July 27, 1992, a bomb explosion devastated the facade of the Rome Vicariate at St. John Lateran. The attack is widely assumed to have been the work of the Italian Mafia, a warning against Pope John Paul II’s frequent anti-Mafia statements. Repairs were completed in January 1996.

The Popes now reside at the Vatican, and since the fifteenth century, St. Peter’s Basilica has hosted most important papal ceremonies. Every year, however, the Holy Thursday liturgy, when the Holy Father symbolically washes the feet of priests chosen from various parts of the world, is celebrated in St. John Lateran.

Lateran interior looking toward doors INTERIOR

St. John Lateran retains, internally at least, its original Constantinian arrangement: a large rectangular hall with impressive nave, flanked by double aisles and terminating in an apse. The Emperor seems to have conceived an edifice to rival the Roman basilicae, or monumental public meeting halls of the imperial city. (In fact, the basilica has provided the model for the great majority of Roman churches, from the earliest to most recent.)

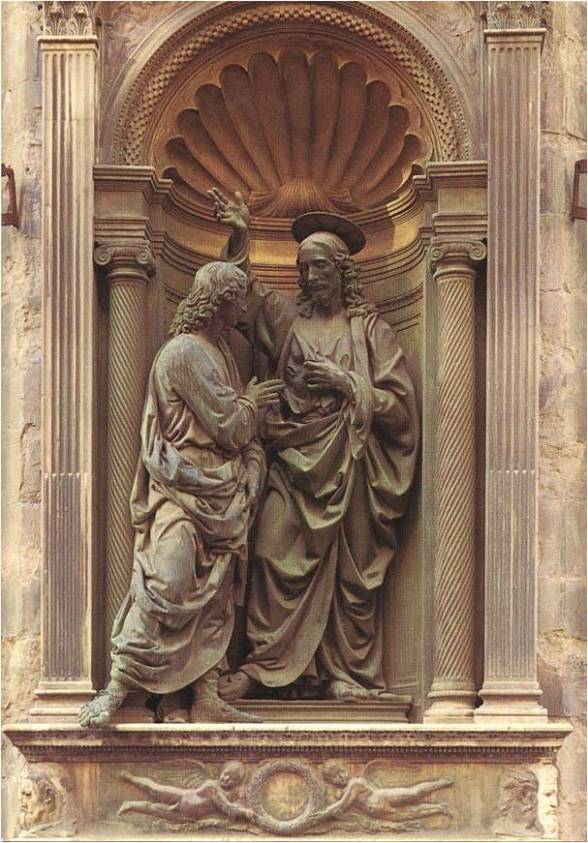

Lateran interior looking toward altar Even Borromini’s Baroque decor does not detract from the impression of an early Christian temple. As usual, Borromini’s genius is not immediately evident. But any visitor will be rewarded by a close examination of details and architectural solutions this resourceful artist managed to execute. The massive statues of apostles which line the main nave (by followers of Gian Lorenzo Bernini), fill their marble-columned niches, fairly bursting with psychological and esthetic power. Above these powerful figures, Pamphili doves (family insigna of Innocent X) are prominently displayed in the pediments, and topped by reliefs by Alessandro Algardi of Old and New Testament scenes, and painted medallions with prophets.

Nave Sculptures of St. James and St. Thomas A gold-leaf coffered ceiling bears the coats of arms of its patron Renaissance Popes, Pius IV (1559-1565) and Pius V (1566- 1572).

Coffered, plastered, and painted ceiling The Cosmatesque-style pavement in polychrome marble, restored by Pope Martin V (1417-1431) appears, somehow, much more recent.

ARTISTIC TREASURES

St. John Lateran contains artistic treasures from every historic period, a tribute to the important role the basilica has played in the history of Rome and of the Roman Catholic Church.

During excavations carried out in 1934-1935 beneath the central nave, significant pagan and early Christian remains were unearthed–floor mosaics, household implements, and even stretches of paved Roman streets. In the atrium, an imposing fourth-century statue of the Emperor Constantine (From the Constantine Baths on the Quirinal) is a reminder of the basilica’s origins, while the central bronze doors (second century) come from the Curia, or Senate in the Roman Forum.

On the second pilaster, between the main nave and far right aisle, we find the fragment of a fresco, attributed to Giotto, of Pope Boniface VIII (1294-1303) proclaiming the first Holy Year in 1300. This fresco originally decorated the papal loggia outside the Lateran Palace.

The lovely cloister dates from about 1215-1230, the work of Pietro Vasselletto and son–and is not to be missed at any cost! The jewel-like mosaics, delicate arches with paired spiral and smooth columns, and oddly “primitive” animal and floral motifs are typical of the Vasselletto duo (who executed another cloister for St. Paul’s Outside the Walls, described in Inside the Vatican, January 1994).

A small museum has been arranged in the Vassalletto cloister. Among other works collected over the centuries by Popes, cardinals and private donors are fragments from the original basilica, a thirteenth-century papal throne, and precious monstrances, tapestries, chalices and vestments.

Lateran apse The apse mosaic, completely redone by Pope Leo XIII (1878- 1903) around 1880, using designs and fragments of the original decorations, are especially appealing. The mosaic includes, besides the bust of Christ the Savior surrounded by angels (perhaps a remnant of the fourth-century original), figures of the Virgin and saints, a magnificent jeweled cross, and pleasant scenes of animals and children frolicking in the River Jordan–as well as tiny portraits of the medieval friar mosaicists, Jacopo Torriti and Jacopo da Camerino, crouched between the apostles in the lower level.

Apse Mosaics Beneath the triumphal arch in the middle of the transept we admire the beautiful Gothic papal altar, which contains a wooden altar where the earliest Popes, from St. Peter to St. Sylvester, supposedly celebrated Mass, and silver busts with remains of the heads of St. Peter and St. Paul. The tabernacle, known to be the last Gothic work executed in Rome, was designed by Giovanni di Stefano in 1367, and surmounted by beautiful frescoes, painted by Barna da Siena in 1369. The confessional below contains the tomb of Pope Martin V (1417- 1431), who was responsible for many of the basilica’s most important embellishments.

Lateran Gothic Baldacchino Entering the transept, we pass from the Middle Ages to the height of late sixteenth-century Mannerism. Pope Clement VIII (1592-1605) employed his favorite architect, Giacomo della Porta, and painter, Cavaliere d’Arpino (see his famous Ascension in the right transept altar) to direct the works. Top Mannerist painters of the day (Cesare Nebbia, Paris Nogari, Cristoforo Roncalli, Agostino Ciampelli, etc.) executed a series of frescoes around the entire left and right transepts, which tell the story of Constantine and St. John Lateran.

Constantine’s Dream After Constantine’s Dream and Victory at the Milvian Bridge, we see his Search for Pope Sylvester I, Baptism, Dedication of the Basilica,Miraculous Appearance of the Savior in the Basilica, and Presentation of Gifts. Much of this legend has been disputed by later historians (who claim Constantine thought little of Pope Sylvester, and waited until his deathbed to be baptized by the Arian Bishop Eubesius of Nicomedia).

This article was taken from the February 1996 issue of Inside the Vatican.

A final note from Infinite Windows blog author: Another spectacular object in the Lateran is the Altar of the Blessed Sacrament, which contains gilded bronze columns dating to the second century that likely decorated an important Roman temple.

Lateran Altar of the Blessed Sacrament

Many of these high quality photos of the Lateran were found at http://www.digital-images.net/Gallery/Scenic/Rome/Churches/Lateran/lateran.html |