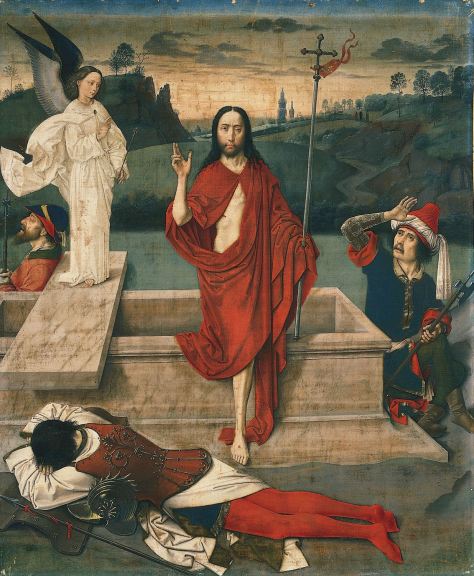

Resurrection by Deiric Bouts, 1455 Distemper on linen 89.9 x 74.3 cm, The Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena

Dieric Bouts was a Northern Renaissance artist whose paintings clearly reflect the naturalism and interest in landscapes and surfaces that is so symptomatic of Flemish works, though he paints in a quiet idiom that is all his own. Bouts’ subtle vision is readily apparent in his 1455 painting of The Resurrection which is now at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena.

Bouts came from Haarlem in the north originally and moved south to Louvain in about 1445, where he established a school, became the city painter and died in 1475. When he painted The Resurrection in 1455 he was well established in his adopted city. The influence of his Dutch background is still apparent in the austere force of this work, but it is mingled with the luxurious color of his adopted home in the south. It is clear that he was heavily influenced by Rogier van der Weyden, as were all of the artists of his time, but he still managed to create his own oeuvre in a distinctive style.

The Norton Simon Resurrection is painted with distemper on linen, an unusual technique called tüchlein which gives the work its matte effect. He used water-based paints, so he was able to apply very thin layers and yet achieve the opacity he desired. Since no primer or ground was used, in some spots the linen shows through where the painting has been abraded, for instance on the angel’s robe. Because of his technique the colors are less brilliant and appear flat. However, there is still evidence of luyster (luster) in the guards’ armor and the trim on their garments and we can see the interest in “stuffs” and “the green grass of the fields” that one writer derided in his critique of Flemish painting. Unfortunately, the pigments that Bouts used have faded over time, as can be seen around the edges of the current frame. The colors originally had more depth and brightness, and as a complete altarpiece it must have been a luminous masterpiece.

The Resurrection is believed to be one of a polyptych consisting of five sections that are now widely scattered. The Crucifixion from the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts in Brussels is the largest painting and would most likely have been the central panel. The left side would have consisted of the Annunciation at the Getty Museum and the Adoration of the Magi now in a private collection in Germany. On the right would be the Entombment from the National Gallery in London, while the Norton Simon Resurrection would be at the bottom right. The linen support makes the sections lightweight so it may have been intended to be a portable altarpiece, but, unfortunately, the patron who commissioned it is unknown.

In The Resurrection we see a typically Boutsian attenuated Christ at the center, a style he learned from observing Rogier’s works. Christ is stepping out of his tomb wearing a deep red robe and carrying a cruciform staff with a fluttering red standard. Christ stares directly at the viewer with a somber expression as he raises his right hand in the blessing pose. Jesus’ countenance is that of the “Vera Effigies, the portrait of the true likeness of Christ” and “he makes the same gesture of blessing as the Salvator Mundi, the Redeemer of the World.” His right hand and foot are visible with the nail holes in evidence, but both his left hand and foot are concealed as he steps out of the tomb with his right foot forward. His left hand is hidden in his robe, although his staff is gripped through the fabric. The hidden hand may denote deference to royalty according to Robert Koch, although this seems questionable in the painting’s context. To whom should the Christ, Risen in Majesty be deferring? It seems more likely that the hidden left hand signifies the fact that the identity of the damned are still hidden and known only by God, not to be revealed until the time of the Last Judgment. That is when Christ will separate the blessed and the damned to his right and left, respectively, according to the Gospel of Matthew. Our word sinister comes from the Latin for left, and this is where the negative meaning of the word derives. The left signifies the damned. This symbolism could also extend to the depiction of Christ’s feet. The right foot forward, stepping out of the tomb, may denote the blessed dead on Christ’s right who will rise to eternal life, while the left foot still within the tomb signifies those who will go to eternal damnation.

There are three guards, one of whom lays face down and seemingly unconscious across the bottom of the picture plane, almost spilling out of the picture while at the same time keeping the eye from running off the front. Another guard sits to the right of the tomb and holds an arm up as if to shield himself from Christ’s glory, while the third appears dazed behind the tomb lid. The separate figures in the painting are placed in a rather zig-zag motion that helps give the painting depth. The tomb cuts straight across the picture from left to right just below the center, parallel with a narrow depression or ravine across the landscape. This compresses the space at the forefront and effectively divides it from the landscape in the distance, making the viewer feel he is on a hilltop. The head of the prone soldier in the forefront nearly meets the lid of the tomb at an angle that serves to frame Christ. The tomb lid lies across the sarcophagus at another sharp angle, thus making a cross, symbol of Christ’s sacrifice. Upon the lid stands an angel in white, possibly Gabriel, with its right hand pointing at Christ and the left holding a staff.

In the background we see a verdant green landscape with a meandering path and an elevated area to the right, while at the left Bouts has added a large rocky outcropping, all adding to the illusion of depth. These two elevations frame the head of Christ and there is a glow on the distant horizon that serves as his halo. Just to the right of Christ’s head in the distance there are two church towers and we can just make out three figures walking in single file on the path towards us. The lead figure is holding an object, and we can be sure that this is Mary Magdalene and the other holy women on their way to clean and anoint the body of Jesus after the Sabbath has ended. All of the figures in the painting appear in arrested motion and the only evidence of movement is the fluttering of the angel’s robes and the pennant that Christ holds, as if a divine wind emanates from the tomb or perhaps from the Risen Christ. The combination of sacred content set within a Flemish landscape is typical of Bouts’ works.

The Resurrection shows the lush landscape that Bouts was later renowned for. The importance of Bouts to the development of landscape painting cannot be overstated. He was the first artist to show a real interest in creating scenic landscapes in his backgrounds. Although his later works show knowledge of one-point perspective, in the Resurrection he uses color, light and atmospheric perspective to create believable settings for his subjects. The glow in the Resurrection emanates from the sky at dawn onto the surrounding hills, but seems to issue from Christ himself. There are few shadows other than a faint one on the left side of Christ’s face. No chiaroscuro here, the entire work is suffused with light.

Dieric Bouts presents us with a timeless image of a moment in sacred history. Here we see a stillness and lack of emotionalism that are the diametric opposite of Rogier’s streaming tears and writhing bodies. Bouts’ ability to impart an air of sacred stillness to his paintings allows the viewer to be drawn in and to meditate deeply but dispassionately upon his subject. When we ponder the serene quietness of Bouts’ Resurrection, we find that we are moved in spite of ourselves. The holy glow that pervades the painting may induce the viewer to acknowledge the presence of a miracle.

[…] Last Supper by Dieric Bouts, an artist we’ve looked at before, is part of the Altarpiece of the Holy Sacrament created for the Confraternity of the Holy […]

LikeLike